D’var Torah – Jan 16

| This Word of the Week is dedicated to Beth Israel Congregation of Jackson, Mississippi and the Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life (ISJL), which were the target of a hate-filled arson attack last weekend. Bizrat HaShem, with God’s help, may our Jewish brothers and sisters in Jackson know our love, may they be strengthened, and may they not only rebuild, but indeed achieve even more than they did before. |

| If you would like to donate to aid Beth Israel or the ISJL, links to both are available here: |

| Beth Israel Congregation |

| Institute of Southern Jewish Life |

| Shabbat Shalom! |

| I pray that this finds you all well. |

|

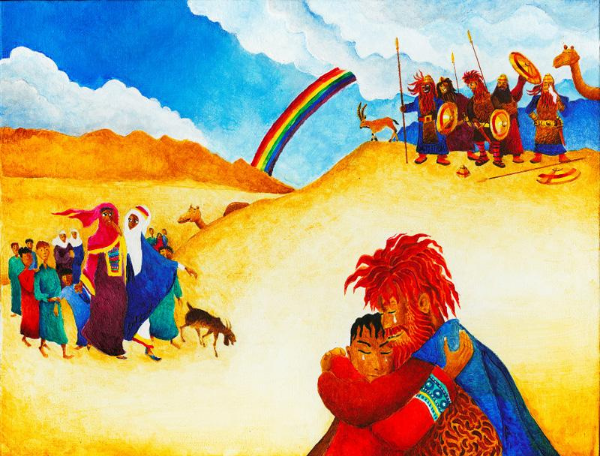

When most people think of this week’s parsha of Va’eira (Exodus 6:2-9:35), it’s usually the first seven of the ten plagues that God sends against the Egyptians that come to mind. However, the parsha also includes “The Promises of Redemption”, which we recall annually at the Passover Seder.

God says to Moses: “I have now heard the moaning of the Israelites because the Egyptians are holding them in bondage, and I have remembered My covenant. Say, therefore, to the Israelite people: ‘I am Adonai. I will free you from the labors of the Egyptians and deliver you from their bondage. I will redeem you with an outstretched arm and through extraordinary chastisements. And I will take you to be My people, and I will be your God. And you shall know that I, Adonai, am your God who freed you from the labors of the Egyptians. I will bring you into the land which I swore to give to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, and I will give it to you for a possession, I Adonai’(*Exodus 6:6-6:8).” Imagine, for a moment, if God had freed our ancestors from Egyptian bondage and gotten them across the Red Sea only to then deposit them in the Wilderness with the parting adieu “good luck to ya.” Despite the rousing seder song Dayeinu where we proclaim that anything that God did for our people would have been more than enough, we know that if it not had been for God’s constant and direct involvement, divine intervention, protection, sustainment, education, and guidance during the forty years in the desert, the Jewish people would most likely have been swallowed up by the sand dunes and consigned to the forgotten and overlooked dust-filled shelves of yellow-tinged history books. Yet because of God’s continual love and attention, we are still here, living as a vibrant and proud people. The Promises of Redemption are far more than a meta-level teaching. They are a model for how we are to conduct ourselves at work, in the community, and at home. To this end, in Kiddushin of the Talmud, we are taught the following: “…A father is obligated in regards to his son…to teach him Torah…and to teach him a trade. And some say: ‘A father is also obligated to teach his son to swim…’”(Kiddushin 29a.10) Rabbi Yehuda drives home the point proclaiming: “Any father who does not teach his son a trade teaches him banditry(*Ibid).” If we simply do the bare minimum, strive only to meet the standard but not go beyond it, and just check the boxes when it comes to being parents, spouses, siblings and children, clergy and laity, and all other places where we are stakeholders, we create a malaise where we all suffer. However, if we do more than what is required of us, just as God did with our people, then the return on our investment is infinite. No matter how good a job we’re doing as husbands and wives, moms and dads, brothers and sisters, sons and daughters, employers and employees, and clergy and laity, parshat Va’eira and the Promises of Redemption therein present a challenge for each one of us – to step up our game, to do more than the minimum, to take our involvement to the next level, and to be fully involved and committed with the people and things we cherish and care about. Let us challenge ourselves to go above and beyond! |

| Wishing you a Good Shabbos and a restful weekend. |

| Bivrakha, |

| Rabbi Aaron |

Shabbat Shalom! I pray this email finds you all well.

Shabbat Shalom! I pray this email finds you all well.